The Data Center Boom

January 28, 2026

During Summer 2025, I spent several months doing research with the amazing Ziqi Guo, supported by a Rock Summer Fellows grant.

Our goal? Learn as much as we possibly could about data centers. (1)

This post is a guide to the data center (or ‘Mission Critical’) industry. We focused our research on planning, funding, and construction — not day-to-day operations — so that’s where this post goes deepest.

Table of Contents

- The Data Center Boom

- Funding a Data Center

- 2.1 How Much It Costs

- 2.2 Data Center Revenue

- 2.3 Funding Sources

- 2.4 REITs

- Building a Data Center

- 3.1 Securing Powered Land

- 3.2 Permitting & Regulatory

- 3.3 Procurement

- 3.4 Operations Basics

- Data Center Futures

- 4.1 Nuclear

- 4.2 Quantum

- 4.3 Underwater, In Space, In the Arctic

- Industry Resources

1. The Data Center Boom

On October 7, 2025, Fortune published this dramatic headline — “Without data centers, GDP growth was 0.1% in the first half of 2025, Harvard economist says.”

Ziqi and I were attending a data center construction conference in Dallas that week.

The vibe of the headline was reflected in the room; long-time industry experts were ebullient at the growth they were seeing, and newcomers (ourselves included) abounded, hoping to share in the boom as other industries flatlined.

While much of the economy has stagnated, demand for data center capacity boomed in 2025, far outstripping supply.

To meet that demand, investors, tech firms, and AI model labs have been raising immense amounts of capital and pouring that money into data center (alternately known as ‘Mission Critical’) projects across the country, leading to huge growth.

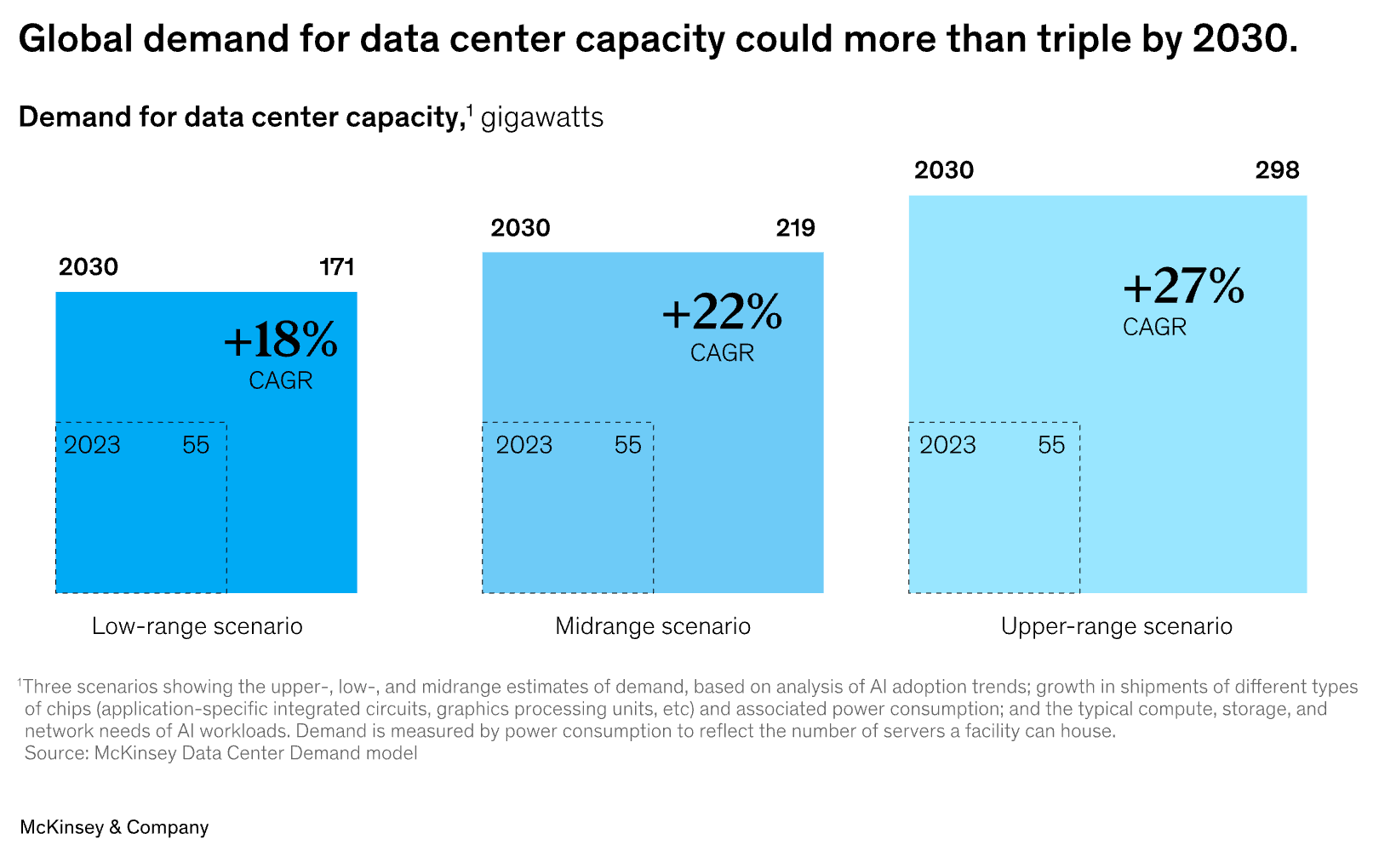

McKinsey & Company projects that global data center capacity demand could more than triple by 2030, implying a CAGR of ~22%:

No matter the exact numbers, the bottom line is clear: the data center market is growing, fast, and people are building new facilities as quickly as they possibly can.

1.1 What’s Driving Demand

The biggest driver of data center growth has been AI.

Companies like OpenAI need data center compute and capacity both to train new models and to use existing models to respond to users’ prompts and questions (a process called ‘inference’).

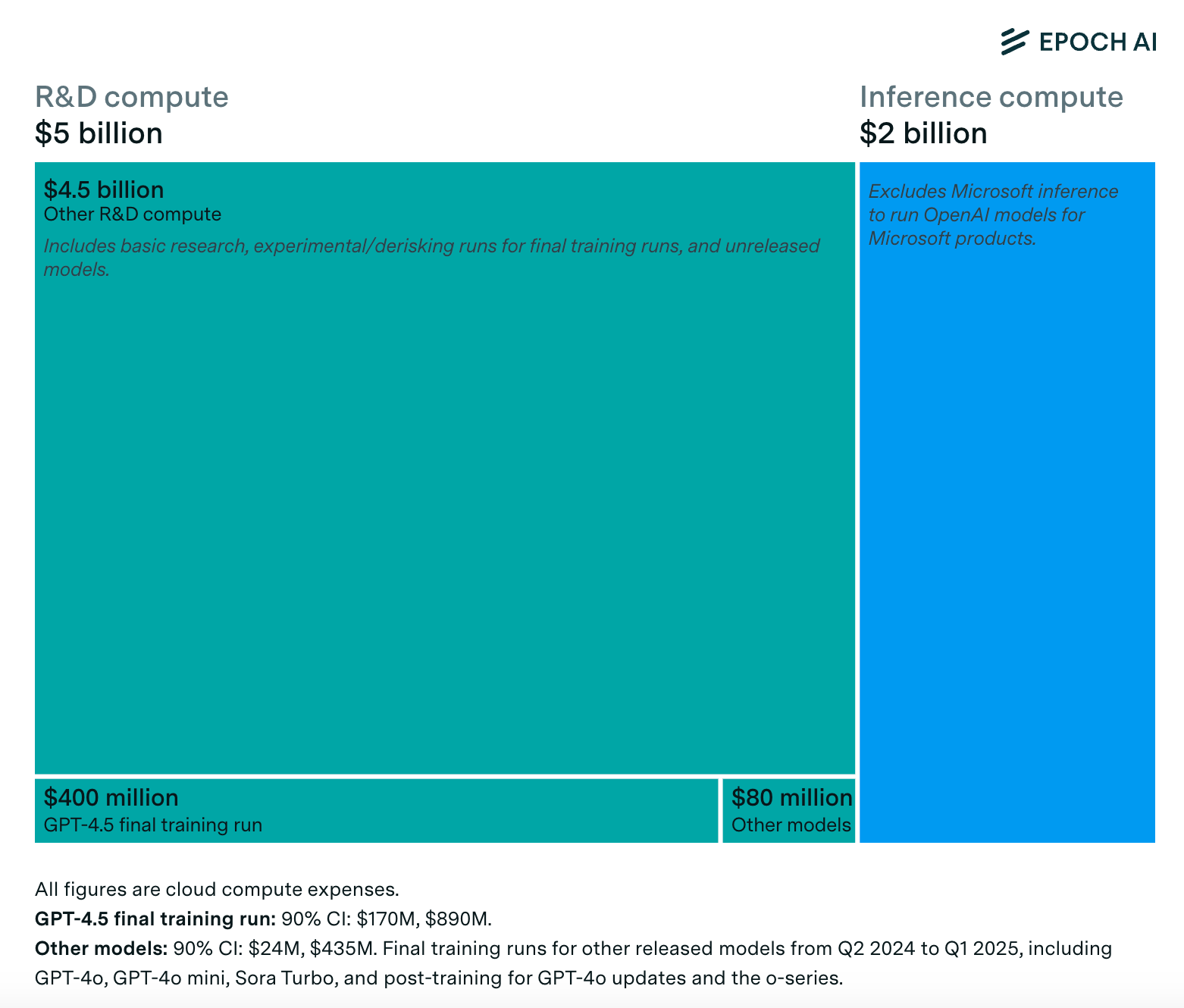

Epoch AI published an interesting chart estimating that most of OpenAI’s spend is concentrated on training models (R&D) rather than on the inference part, at least for now:

Other big drivers of demand include the continued shift from on-premise (where companies have their own servers that they manage) towards cloud-based software.

And finally, cloud providers like Google and Amazon have been scaling up their data center footprints around the world to make sure that end-customers, no matter where they are, can have fast access to their data, software, and other cloud services.

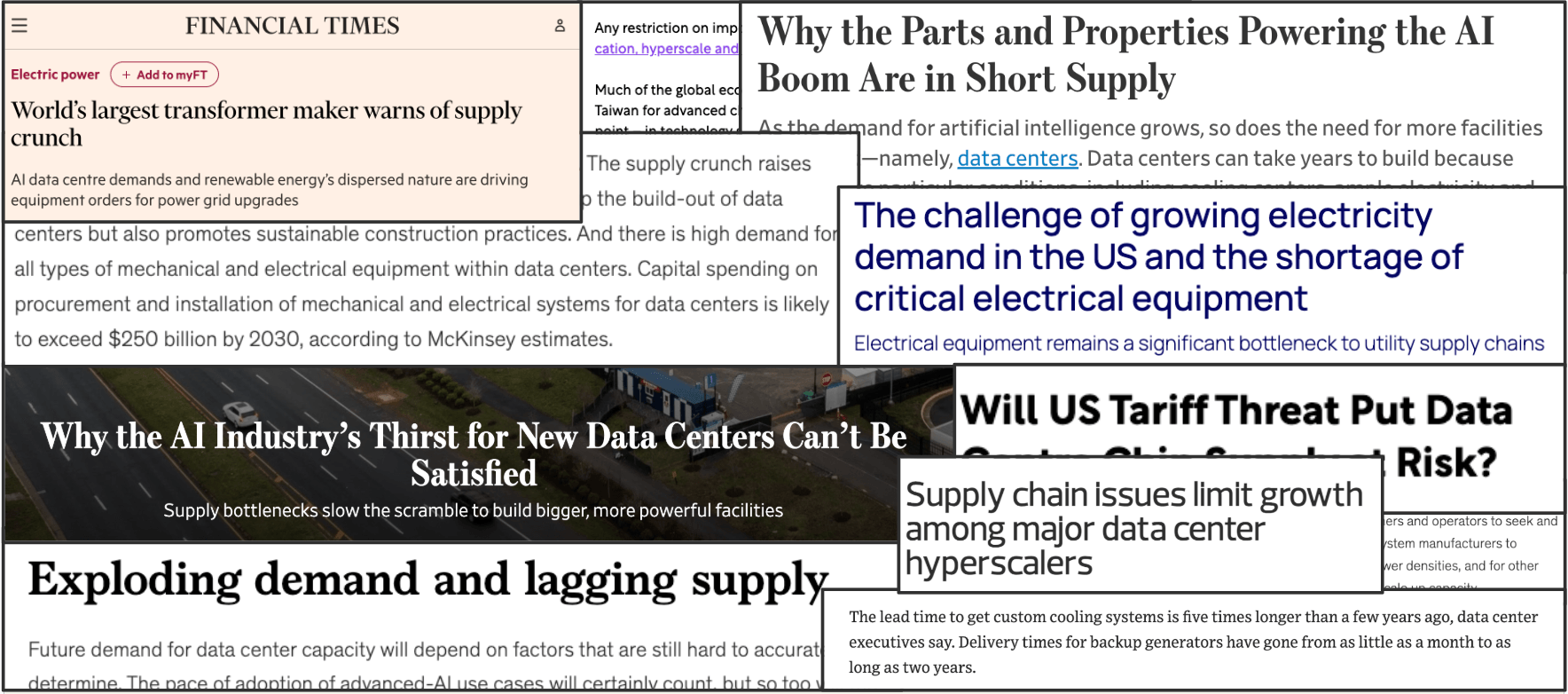

While data center supply is increasing rapidly, it’s not particularly elastic. Building data centers takes time and the rapid boom has meant that equipment is backlogged, power is scarce, and regulators are overwhelmed.

So, now that we know that data centers are booming, and what’s driving it, let’s cover the basics - what types of data centers exist, and who’s actually building what.

1.2 Types of Data Centers

Not all data centers are created equal.

While there are many flavors, most can be categorized into one of three buckets:

- AI data centers: Huge, often in the middle of nowhere, most of what you see in the news

- Co-location data centers: Data centers built by data center companies, who then lease capacity to tenants

- Enterprise/on-prem data centers: Data centers that are managed by companies themselves for their own needs

1.2.1 AI Data Centers

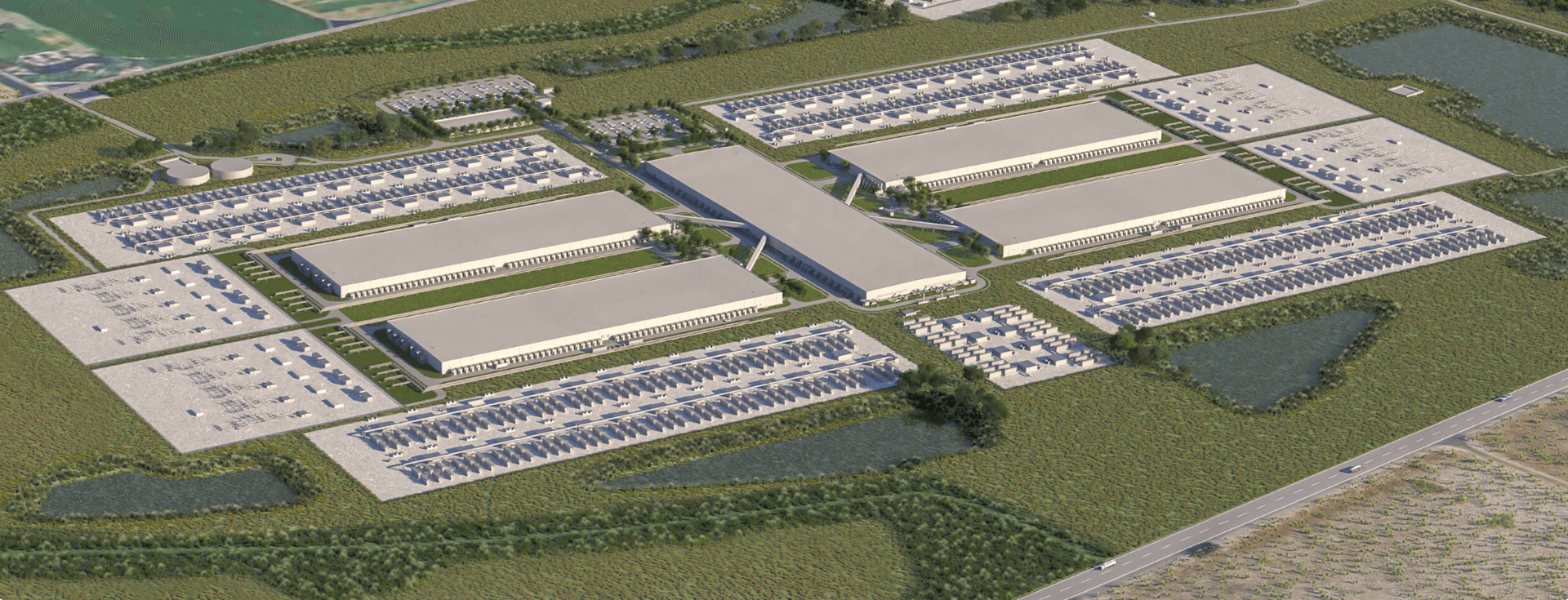

When you think about AI data centers, you should imagine something like Meta’s $10B AI data center in Richland Parish, Louisiana (shown in this mockup):

These are big! Huge, even.

AI data centers are typically built or commissioned by leading cloud / AI companies (e.g. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta), or sometimes by specialized infrastructure firms under contract.

AI companies use these data centers for a mix of AI training (‘teaching’ the model) and for inference (responding to user prompts).

Because AI training and inference are compute intensive (and expensive), these data centers tend to invest heavily in the latest and greatest technology to maximize efficiency.

For example, AI data centers often use very powerful GPUs (Graphical Processing Units, a type of chip used for AI compute) that are difficult to keep cool. According to Schneider Electric, NVIDIA’s latest GPU racks require around 130kW of power per rack, with next-generation hardware expected to reach 240kW — compared to traditional server racks which required just 10-15kW. As a result, AI data centers also use ‘liquid cooling,’ a technology that is more powerful and efficient (but also, more expensive) than traditional fans and other air-based cooling systems.

For many data centers, proximity to users is important to limit latency, but for model training (which, as we saw above, makes up a bigger portion of the spend than inference), location doesn’t really matter. As a result, AI data centers are increasingly being built in remote places to capitalize on affordable power or friendly governments, rather than being close to urban centers.

Thus, how Meta’s huge data center ended up in Richland Parish, which has a population of 20,000 people.

1.2.2 Co-location Data Centers

Co-location data centers (“colos” for short) are typically built and operated by a third-party data center developer, like Vantage, NTT, or QTS.

Some of these facilities are ‘built-to-suit’, where the data center is constructed to meet the needs of a single, pre-determined tenant (think an AI/cloud company, e.g. Amazon or Google, or a large enterprise, e.g. a bank). These tenants sign hefty leases and, in exchange, the third-party developer builds and operates the data center based on their specifications.

While ‘build-to-suit’ is increasingly common, many co-location data centers are also multi-tenant. In a multi-tenant data center, many smaller companies will share common infrastructure (power, cooling, connectivity), but have separated secure “cages” or zones for their actual servers. Here’s a picture of what that looks like from CoreSite:

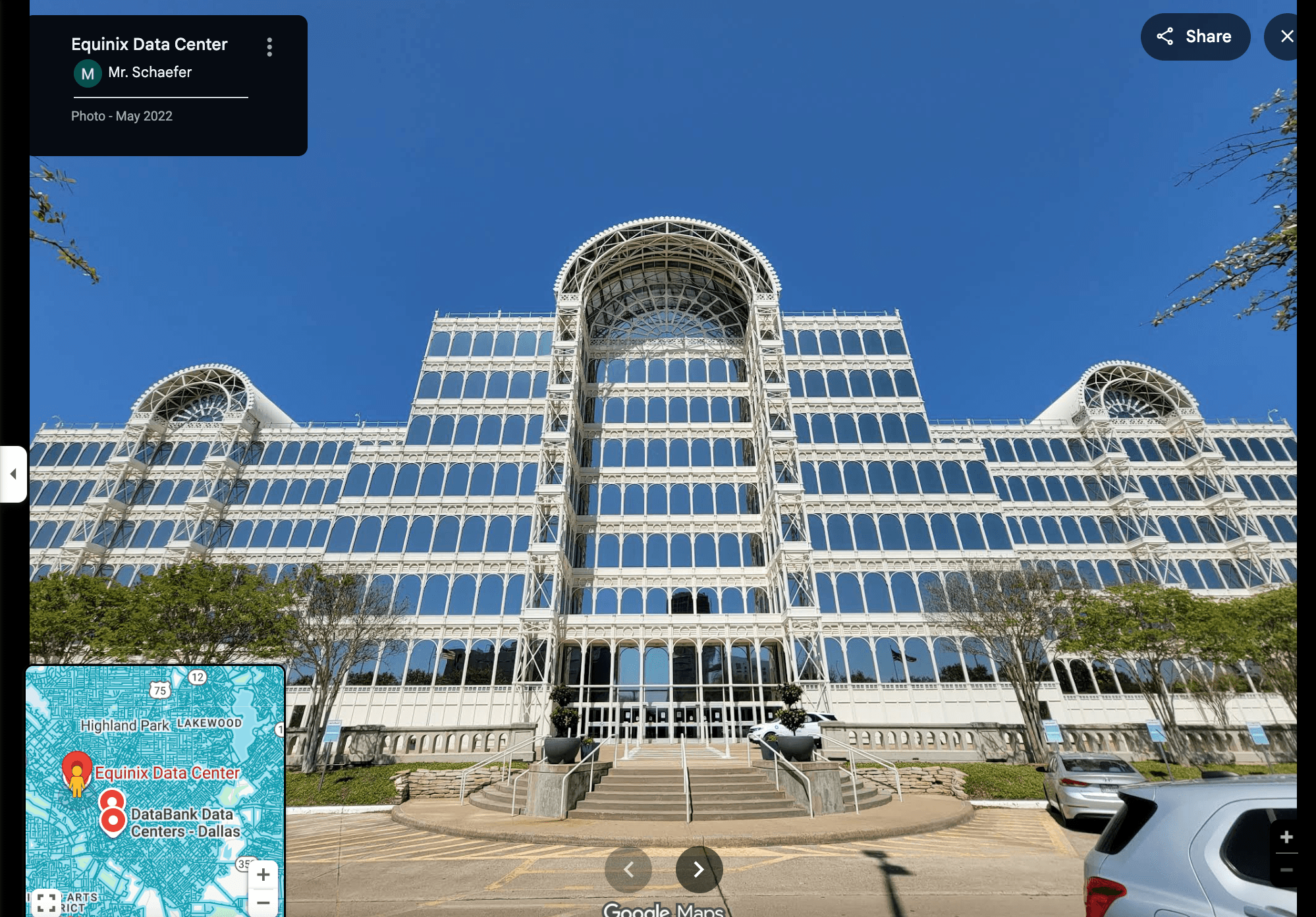

These also aren’t always giant data center campuses like we see with all the new AI builds. Here’s an Equinix colo data center in downtown Dallas; it blends right in:

Buying space in a colo data center requires much lower upfront capital investment and expertise than your own facility, so it’s better for early stage or smaller companies who prefer flexibility over control.

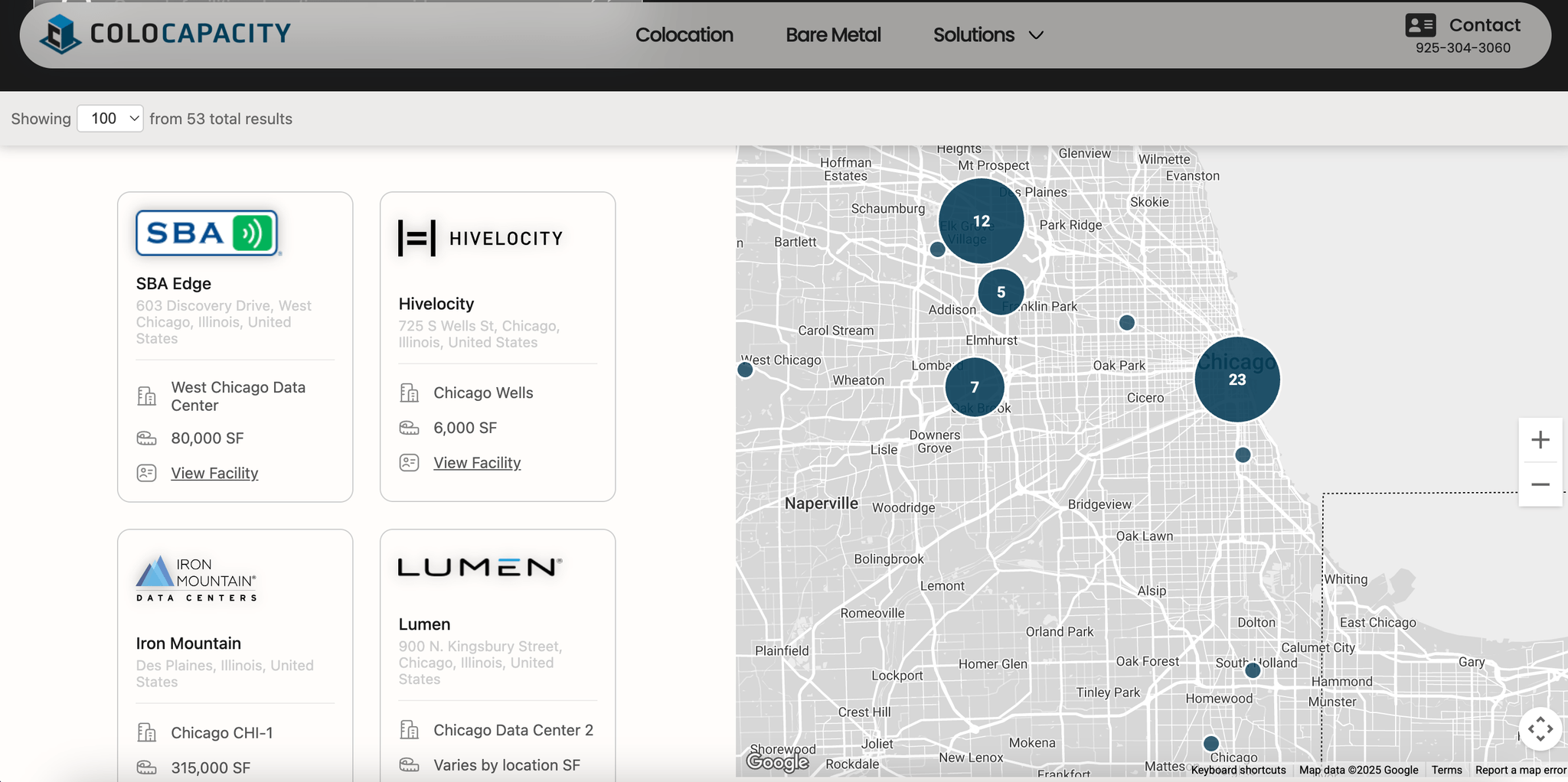

Because colocation is functionally a marketplace (matching companies with colo capacity), there are about a million websites that help you discover colocation data centers and get quotes, including but not limited to ColoCapacity, DataCenterMap, and QuoteColo.

These sites can be helpful to get a sense of the industry scale (and, you’ll often be surprised to realize you live near data centers that are hiding in plain sight!)

1.2.3 On-Premises / Enterprise Data Centers

Enterprise data centers are typically owned and operated by a company for its internal use. These data centers tend to be smaller, less cutting edge, and situated in or near corporate campuses or urban centers.

Many enterprises are migrating away from fully on-premise setups (where they own their own servers at their own site) to hybrid or cloud models, due to flexibility and scale issues. That said, on-prem facilities can be lower cost and give companies much more control.

Now that we’ve covered the different types of data centers, let’s look at who’s actually building and operating them. The data center ecosystem involves many different players, each with distinct roles in bringing these massive projects to life.

1.3 Key Ecosystem Players

We’ve already mentioned some of the data center players, but let’s break it down, covering:

- Hyperscalers & AI Giants

- Data Center Companies

- Real Estate Developers

- General Contractors (Construction Firms)

- Subcontractors / Trade Partners

- Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) Firms

- Equipment Suppliers

Not included here are investors, who will be featured in the next section on Funding a Data Center.

1.3.1 Hyperscalers & AI Giants

The definition of ‘hyperscaler’ is blurry, but people generally use the term to talk about companies that offer compute resources at scale. Originally, this term was used for the cloud service providers - Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure), and Google (GCP) - but now people often use it when talking about Oracle, Meta, OpenAI, Anthropic, and more.

A single hyperscaler client is often the anchor, or even sole, occupant of a data center facility or campus. Because hyperscalers consume so much capacity, their decisions (where to build, how much to lease, what technologies to deploy) strongly influence the rest of the value chain.

While hyperscalers sometimes build and manage their own data centers, they often also lease from data center companies.

1.3.2 Data Center Companies

Data center companies are entities whose primary business is to own, develop, and manage data centers. They lease capacity in their data centers (typically defined by the amount of power, rather than physical space or square footage) to their tenants, which include hyperscalers.

To facilitate this, data center companies typically need to raise huge amounts of capital, and many have ties to or backing from large investors. Many also operate as REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), which is a tax-advantaged structure.

While there are many smaller data center firms, a few of the biggest include:

- Equinix — Publicly traded (NASDAQ: EQIX) global data center firm

- Digital Realty Trust — Publicly traded (NASDAQ: DLR) global data center firm with >300 properties

- QTS — Data center company acquired by Blackstone for $10B in 2021

- Vantage Data Centers — Data center company most recently funded by a $9.2B equity investment from DigitalBridge Group and Silver Lake Partners

This space has a very long tail - there are lots of single-data center companies that have sprung up to take advantage of the boom. We can expect to see more and more consolidation within the data center space as smaller providers are rolled up into larger organizations with better economies of scale and access to investors.

1.3.3 Real Estate Developers

Companies like JLL and CBRE have benefitted enormously from the data center boom, helping hyperscalers and data center companies to identify and acquire promising sites for data centers.

Many smaller opportunistic real estate developers acquired land parcels that had access to power or were near transmission lines and have flipped those properties profitably as power has become an increasing constraint on site selection.

1.3.4 General Contractors (Construction Firms)

The growth in data centers has also been a boon for construction firms. Typically, construction projects operate with one ‘General Contractor’ or ‘GC.’ The GC interfaces with the person paying for the project (the ‘Owner’, often a data center company), finds subcontractors to perform pieces of the project, and manages the whole operation.

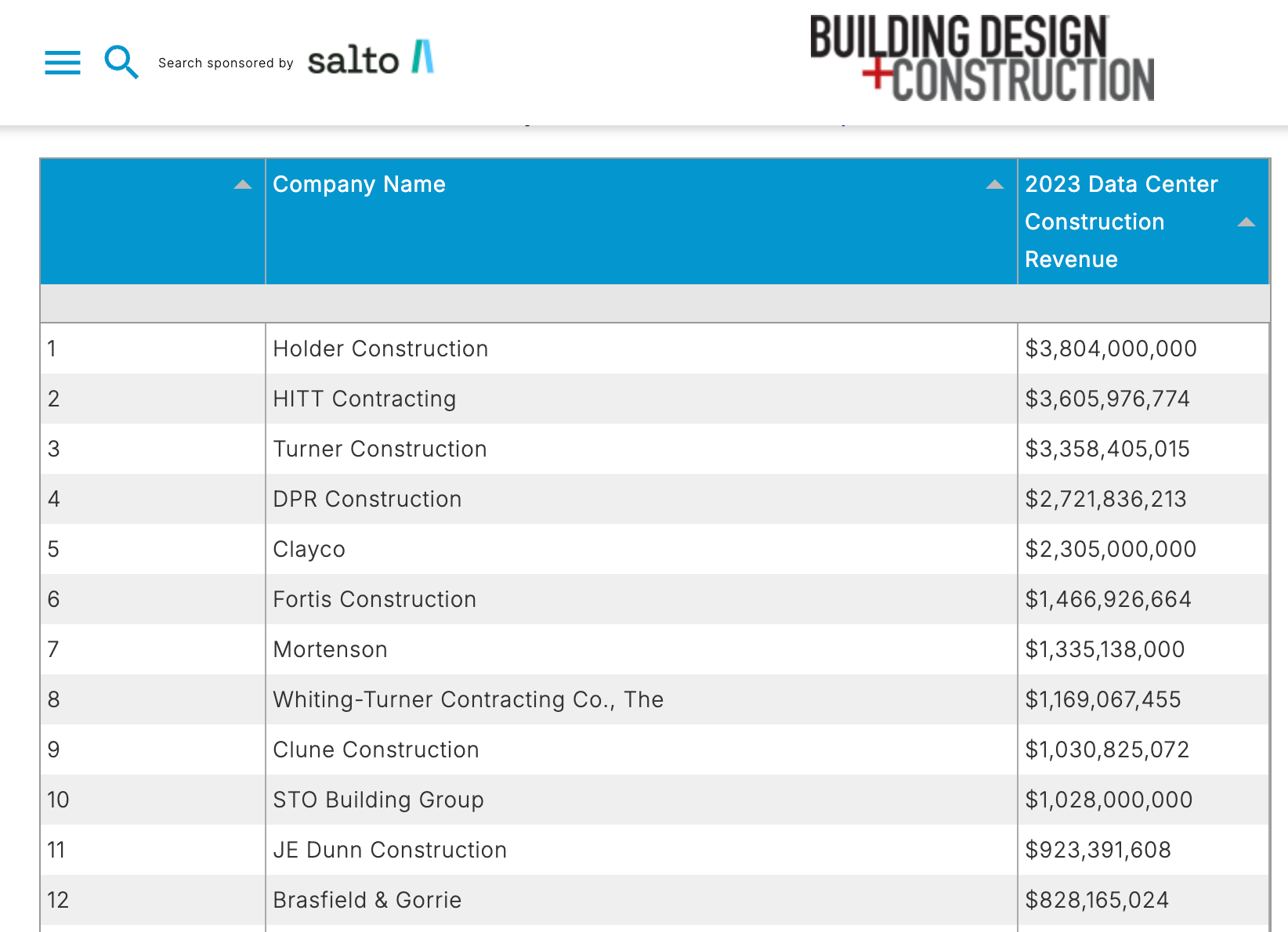

Building Design + Construction publishes a list of the top data center construction firms (GCs), which is led by companies like Holder Construction, HITT, Turner, and DPR. Each of these firms had >$2.5B in revenue from data center construction in 2023.

General Contractors typically make money by charging a fee on the total project costs.

1.3.5 Subcontractors / Trade Partners

While the General Contractor acts as the ‘quarterback’ of a data center construction project, they hire a large number of subcontractors, sometimes also called trade partners, to execute much of the actual construction work.

For example, a GC might hire a specific “sub” or “trade partner” for each of HVAC, roofing, and lighting.

1.3.6 Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) Firms

Depending on the project size and scope, the owner may also hire an EPC firm to help.

While the General Contractor leads the construction part, the EPC firm manages the project from start to finish, beginning with design through when construction fully wraps, often acting as an intermediary between the owner and the GC.

Examples of EPC firms with strong data center practices include Kimley-Horn, Burns McDonnell, Jacobs, or WSP.

1.3.7 Equipment Suppliers

Data centers require large amounts of MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) equipment.

Popular vendors for electrical parts include companies like Schneider Electric, ABB, Vertiv, Eaton, and Toshiba.

For electric generators, key suppliers include companies like MTU/Rolls Royce, Cummins, and Caterpillar, supported by a large network of distributors. Natural gas turbines, which support behind-the-meter energy projects, are made by companies like Siemens, GE Vernova, and Mitsubishi.

Server makers are companies like Dell or HPE, while chips are made by Nvidia, AMD, and Intel.

2. Funding a Data Center

Data Centers are expensive to build, so funding typically has to be secured upfront. This section will focus on where that money usually comes from and how it gets spent along the way.

2.1 How Much It Costs

Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, estimated that a typical data center costs $60-80B per GW, and that $40-50B of that spend is the electronics - servers, GPUs, and more. This means construction alone - getting to a ‘powered shell’ costs $20-30B. Others (like Barclays analysts) have found that number a bit high.

In our research, we heard a more conservative rule-of-thumb: A typical 1 gigawatt (GW) AI data center costs $10-15B to build. After the building is constructed, the end-user will typically invest 2-5x more than that (usually another $20-50B) to fill it with servers and GPUs. (For more on how data centers make money from leasing this capacity, see Data Center Revenue.)

To provide a real-world example, the Stargate project by OpenAI, Oracle, and Softbank has allocated $500B to bring 10 GW online, so $50B per GW, but likely benefitting from economies of scale.

This pricing reflects the cost to build AI datacenters that use top-of-the-line technology, like the latest GPUs and liquid cooling. Not every data center needs this kind of technology, so not every data center will cost this much.

However, this is pretty representative of the scale and costs of most of the data center builds that are making headlines today. It’s staggering.

2.2 Data Center Revenue

When data center companies like T5 or NTT build data centers, they’re typically planning to make money by leasing that capacity to a client. That client is typically a hyperscaler or AI company like Amazon, Google, or Anthropic. Other companies like Equinix who do more colo data centers will expect to have multiple clients. This requires more management effort, but those companies pay higher rents since they have less negotiating power than the hyperscalers.

While the data center itself is difficult, expensive, and slow to build, data center leases, once secured, are great revenue streams as far as commercial real estate goes.

Data center leases have long time horizons, typically 5-10 years, but sometimes longer for ‘build-to-suit.’ Most include built-in rent escalations, either by a fixed percent or tracking inflation. And finally, they’re typically ‘triple net’ (NNN) leases, a term from commercial real estate for where the tenant pays for rent plus three expenses that might otherwise ‘net’ against the landlord’s profits: property taxes, building insurance, and maintenance/repairs. In other words, the landlord gets more money, and the tenant absorbs more risk.

That said, leasing data center capacity is not without risk, particularly given the speculation about the AI bubble. Microsoft pulled out of several leases in mid-2025, providing a sobering reminder to data center companies of the risks: once your tenant moves in, it’s great.

But, you really need a firm tenant commitment before you invest the CapEx.

2.3 Funding Sources

To fund that upfront investment, data center projects raise a lot of money!

Recall: for a 1GW project, you’ll need $35-80B depending on who you ask.

Typically companies use a blend of debt and equity financing. Debt can be provided by banks or by private credit (loans from private non-bank institutions like PE funds).

Equity often comes from private equity firms, many of which have dedicated infrastructure funds focused on this topic, or from public equity markets, such as via publicly-traded REITs (more on this in the next section).

The scale of funding needed is part of why we’ve seen close alignment between data center companies and Private Equity companies that can provide some of that capital. For example, Vantage Data Centers was launched by and remains heavily funded by Silver Lake, and QTS was acquired by Blackstone.

2.4 REITs

A REIT, or a real estate investment trust, is a company that owns and operates income-producing real estate, such as a data center. REITs have an extremely unusual tax structure where, as long as they pay out 90% of their taxable income to shareholders as dividends, they don’t pay corporate income tax.

Many of the largest data center companies are publicly-traded REITs, such as Digital Realty and Equinix.

Investors like REITs because they have tax advantages and tend to provide a stable source of income, since nearly all the revenue from leases is paid out as dividends. REITs are a useful financing structure for capital-intensive data center projects because they allow companies to raise large amounts of money from investors who are looking for ways to capitalize on the digital infrastructure boom.

Now that we’ve covered how data centers are funded, let’s move from finance to construction — how do you actually build one?

3. Building a Data Center

Ok, so assuming you can secure funding, how do you actually build a data center (ideally, profitably)?

3.1 Securing Powered Land

An important caveat to this section: we focused mainly on construction in our research, which means the site and power source have already been secured. Site selection and power acquisition are complex topics; this will only be a high-level view of each.

3.1.1 Site Selection

The ideal site depends heavily on the purpose of the data center. If you’re building an AI data center that you expect to be used for training large language models and nothing else, you should build your data center in the middle of nowhere, such as Richland Parish, Louisiana or the Texas Panhandle.

If your data center is going to be used for cloud computing, it’s valuable to be close to customers (or, your customers’ data centers) to reduce latency. Several major cities have large data center ‘hubs’ just on their outskirts: take for example Northern Virginia’s Data Center Alley or Chicago’s Elk Grove Village.

Other considerations include things like geographic risk (e.g. climate risk), room for expansion, connectivity/fiber access, local costs and tax rates, availability of staffing, and more.

But, the most important consideration of all in site selection is access to power, including understanding the local grid and transmission lines.

3.1.2 The Power Problem

Power access is the single biggest holdup — and biggest risk — in data center construction today. Power needs to come first, long before any shovels go into the ground.

Tier-1 markets (Northern Virginia, Northern California; places with high demand and existing data centers) are power-constrained. “Powered land” can take 2–5 years to secure. Even then, access to power usually scales up over time, so full connection to the grid is even further out, as long as 9-11 years. It also requires multiple levels of regulatory and technical approval.

3.1.3 Our Energy Infrastructure

Something I found confusing about data center power at first is that there are multiple layers of power authorities and brokers who you have to go through.

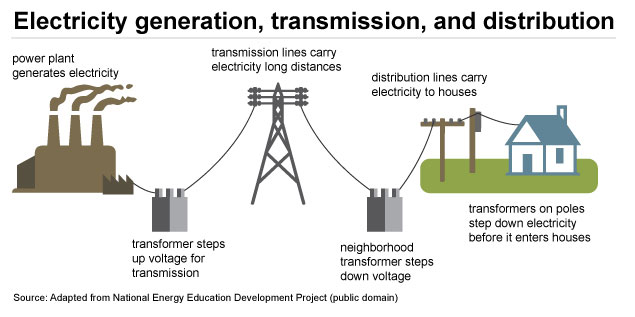

First, let’s think about the different parts of the power system: generation, transmission, and distribution.

As a consumer, we’re used to interacting with the power utilities who distribute the power. These are companies like the Southern Company, Georgia Power, Dominion Power, Duke Energy, PG&E, Eversource, etc. - every region has their own set of players. Some of those utilities, but not all of them, also generate and transmit their own power. Others purchase from power generation companies or from a wholesale market.

For the grid to be stable, supply has to meet demand, so local electricity networks are connected into larger regional ones, and governed by an overarching federal agency, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The regional organizations are called either Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) or Independent System Operators (ISOs). RTOs and ISOs are historically different, but today the terms are used basically interchangeably, which adds to the confusion.

Most people have never heard of RTOs and ISOs, which also have names that are their own abbreviations, like PJM (Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland) and ERCOT (Electric Reliability Council of Texas).

Source: https://www.ferc.gov/power-sales-and-markets/rtos-and-isos

Source: https://www.ferc.gov/power-sales-and-markets/rtos-and-isos

RTOs and ISOs help to keep the electric grid in each region reliable by balancing supply and demand, helping coordinate wholesale electricity markets (so companies that distribute but don’t generate can buy power), and managing interconnection for new projects that will place a large load on the grid (of which data centers are very big ones!).

For a data center, typically they’ll have to work with the RTO or ISO to get an Interconnection Agreement, which is basically approval to connect to the grid under certain conditions and a specified timeframe.

So, the RTO or ISO approval gives you the right to take power from the grid. Next, you also need a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), which is the right to buy power from a specific generator. This is your commercial contract, usually with a utility like Duke Energy, and includes details like pricing.

Because there’s such a flood of demand for data centers, ISOs, RTOs, and utilities have seen a flood of inbound interest and applications, so the timeline is slowed both by the grid’s capacity to accept new large projects and by the time it takes to manage approvals.

As if that wasn’t enough, transmission capacity is emerging as a critical choke point. U.S. networks weren’t built for concentrated 1+ GW loads; most transmission lines were built for much lower voltages, and lines that overheat can cause cascading failures. As a result, this can create reliability risks; upgrades are capital intensive and slow.

3.1.4 Behind the Meter

The challenging reality is that demand for data centers is far outstripping the availability of power.

As a result, we’re also seeing a huge growth in ‘Behind the Meter’ (BTM) data center investment, where companies build new power sources alongside data center developments, providing energy without ever even connecting to the grid.

This allows companies to skip the long waits to connect to the grid. While some of these plants use renewables or even nuclear, the majority of these new plants rely on natural gas. According to a call between Latitude Media and McKinsey, there are estimates that 25-33% of incremental data center demand through 2030 will be met by BTM power.

However, even if BTM avoids grid connection waits, equipment can still be a constraint: strong demand for natural gas-fired turbines has led to wait times of up to 7 years.

Market shifts have increased interest in LNG, restarted nuclear/coal assets, and stranded power opportunities, especially in places like Texas with lighter red tape.

3.2 Permitting & Regulatory

3.2.1 SB-6

Texas’s Senate Bill 6 (often just called “SB-6”) offers an interesting case study of the regulatory risks associated with building data centers, as well as the challenges that the huge growth in activity have created for regulators.

Data center investment has flowed rapidly into Texas due to its relatively quick permitting process and openness to data center developments.

However, in February 2025, Texas introduced SB-6, a bill framed around mitigating the risk of another massive grid failure, like what Texas saw in 2021 during the unexpected deep freeze. The initial version of SB-6 included a ‘kill switch’ provision that said that any entity that uses a lot of power (75 MW and above) had to give the local regulator, ERCOT, the ability to remotely cut off power if needed.

This provision was seen as a huge risk to data center operators, for whom reliability is absolutely paramount. While the ‘kill switch’ was softened meaningfully over time to make it so that large energy users must be ‘curtailment ready’ — so have the capacity to reduce their load remotely if needed — but data center owners retain operational control.

“Large load” customers now also need to pay a $100K fee for an initial utility screening, a move intended to cut down on the large number of speculative but unserious requests clogging the queue, and requires other financial commitments for companies to be granted reserved power capacity.

3.2.2 Community Pushback

Community pushback to data center projects has also been growing. For example, in September, residents of Tarboro, North Carolina voted down a $6B data center campus.

Concerns typically include worry about having such a large development in their community, noise, and concerns about environmental impact and that data center energy use will raise their utility bills.

While data centers typically produce a large amount of tax revenue, they typically don’t provide many jobs; while construction tends to provide hundreds or thousands of temporary roles (the Tarboro data center would have provided 500), long-term operation of a data center tends to only create a handful of roles for technicians and security.

3.2.3 Economic Impact Modeling

To try to counter this pushback, we’ve seen data center companies and their financial backers invest increasingly in lobbying and building local relationships with town and city councils.

Many companies also try to use economic impact modeling to quantify the scale of the benefit to the locality; Here’s an example from a proposed data center in Oregon.

3.3 Procurement

Once you’ve decided to build a data center, have designs, have funding, and have (or are close to having) a tenant, you can start working with your contractor to kick off procurement: getting all the supplies you need to actually build.

3.3.1 The Basic Process

For a data center, you need to procure all the standard construction materials - steel, roofing materials, doors, etc. - but you also need a lot of additional electrical and cooling equipment to power and chill the servers and GPUs you plan to put inside.

Key equipment includes generators, switchgear, transformers, breakers, PDUs (power systems), and UPS (uninterruptible power systems), and cooling systems, which include chillers, cooling towers, and more.

Each piece of equipment has its own lead time - the time between when you order and when it arrives on site - and many of these can be 12-24 months or longer, especially for custom-built electrical gear. Procurement is critical because delays in one piece can hold up the entire project.

Project managers and engineers often work backwards from when they need equipment installed, then order months or even years in advance, sometimes before they’ve even broken ground on the site.

3.3.2 The Supply Chain Slowdown

The huge boom in mission critical construction (see Section 1), on the heels of COVID-related supply chain disruptions, has led to severe supply chain shortages.

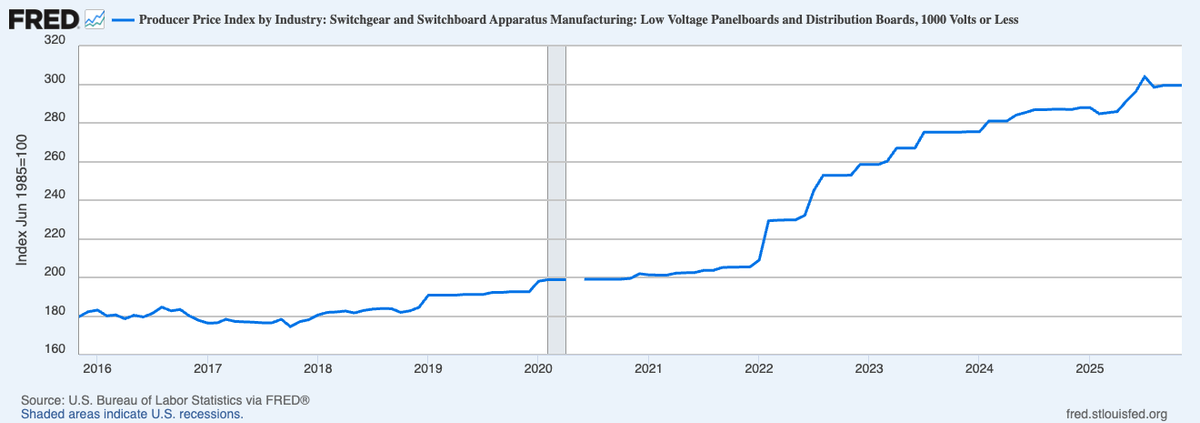

Particularly impacted have been the electrical equipment, like switchgear — a giant box filled with fuses, switches, and other power conductors. Because data centers require lots of energy, they require lots of switchgear.

But, the companies who make that equipment, like Vertiv and Schneider Electric, have struggled to (or, haven’t wanted to) scale production up quickly to keep up with demand. They’ve also gained extraordinary negotiating power in deals, including demanding upfront payments and pulling back on warranties.

As a result, lead times and prices have both jumped upward in the last few years. Here’s the price index for switchgear, as an example:

3.3.3 Procurement Strategies

Most procurement falls into two categories: “OFCI” (Owner Furnished, Contractor Installed) or “CFCI” (Contractor Furnished, Contractor Installed). Traditionally, owners buy expensive equipment like generators and chillers themselves (OFCI), while contractors handle smaller items (CFCI).

Given the long lead times, we’ve seen two trends emerging. Many owners are buying and stockpiling long-lead equipment in advance, paying for storage rather than risking project delays. At the same time, CFCI is on the rise as new entrants to the data center space lean on contractors’ procurement expertise.

With equipment shortages, companies are getting creative. Large firms sometimes use supplier relationships to ‘skip the line,’ while others order key parts months or years before installation — sometimes before breaking ground. Many have also centralized procurement rather than delegating to subcontractors, and some use modular, pre-fabricated equipment to reduce on-site delays (more on modular construction below). As a last resort, some re-sequence construction to install generators later, or use temporary power for inspections while waiting for equipment to arrive.

3.3.4 Staffing

Another notable constraint and challenge within the data center construction space has been the availability of talented and trained electricians. This is particularly true for high-voltage projects like upgrading transmission lines.

This is exacerbated by both the sudden boom and the tendency of AI data centers to be built in remote areas with limited local talent pools. According to Uptime Institute surveys, more than half of data center operators (53-58%) report difficulty finding qualified candidates for technical roles, a challenge that’s even more acute in the construction phase where specialized electricians are essential.

3.3.5 Modular Construction

One growing trend within data center equipment selection and procurement is ‘Modular.’ Depending on who you’re speaking with, this could mean many things, since many aspects of data center construction can be modularized.

The most common usage is in reference to Modular containers (think: train cars) that are packed with MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) equipment, made by companies like Cupertino Electric.

Modularizing can be helpful because it allows some of the construction to move off-site, making it easier to source electricians and improving on-site safety. However, it can be more expensive and less flexible than more standard layouts.

3.4 Operations Basics

While our research focused on construction, here are a few interesting things to know about operations. Once a data center is operating, two things are paramount: efficiency - usually measured by Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), and reliability.

PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) is the most commonly cited efficiency metric. It measures how much power actually reaches the IT equipment versus total facility power:

PUE = Total Facility Energy Usage / IT Equipment Energy UsageA PUE of 1.0 would mean all power goes to servers (impossible in practice). A PUE of 1.2 is considered excellent and is typical of what clients expect from new builds.

Reliability is paramount for a data center. Downtime can be extremely expensive or result in data loss. Data centers invest heavily in monitoring systems, backup power, and physical security (fencing, surveillance, access control). Data centers also all have Building Management Systems (BMS), software that monitors the status of the equipment to ensure prompt interventions when needed.

4. Data Center Futures

4.1 Nuclear

Nuclear power has emerged as a popular solution to data center energy demands. Unlike solar and wind, which only generate power when the sun shines or wind blows, nuclear runs 24/7 without carbon emissions.

2024 and 2025 saw a flurry of nuclear deals:

- Microsoft signed a 20-year deal to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1 (the reactor that didn’t melt down), targeting 2028

- Amazon partnered with Talen Energy to power a data center directly from a Pennsylvania nuclear plant

- Google signed a deal with Kairos Power for small modular reactors (SMRs)

- Oracle announced plans to power a 1 GW data center with three SMRs

SMRs are generating particular excitement. Traditional nuclear plants are massive (1+ GW), take over a decade to build, and cost tens of billions. SMRs are smaller (50-300 MW), can be factory-built and shipped to sites, and have simpler safety systems. Companies like NuScale and X-energy are leading development, though none are operating commercially in the U.S. yet.

The challenges are real: regulatory approval takes years, nuclear construction has a history of delays and cost overruns, and public perception remains mixed. But, the combination of AI power demand and climate goals has made nuclear more attractive than it’s been in decades.

4.2 Quantum

Quantum computing is a longer-term wildcard for data centers. These machines work fundamentally differently than normal computers and can theoretically solve certain problems much faster, but they require extreme cooling (near absolute zero) and careful shielding from interference.

Today, quantum computers aren’t replacing data centers; they’re being housed inside them. IBM, Google, and others operate quantum systems that users access over the internet, with regular computers handling the interface.

For now, quantum remains a tiny, specialized corner of the data center world — useful for narrow research applications but nowhere close to replacing GPUs for AI. The more immediate concern is security: quantum computers may eventually be able to break today’s encryption, which is pushing companies to adopt new encryption standards now.

Given that all the major tech companies are investing heavily, quantum is worth watching over the next 10-20 years, even if it’s not reshaping data centers today.

4.3 Underwater, In Space, In the Arctic

We’ve seen a recent growth in novel and crazy-feeling data center concepts, and associated startups: Data centers underwater and data centers in space are two prominent ones.

These are already more real than you might expect:

- Microsoft’s Project Natick created and tested an underwater data center in intentionally harsh conditions to understand viability and even test that the data center could be securely retrieved from the water. China also actively uses this as a tactic.

- In November 2025, Starcloud launched a GPU on a satellite as an early prototype, and used it to train a model and run Gemini in space.

Both of these models drastically reduce the cost to cool the data center, and space also provides access to more efficient solar power. However, as you might expect, issues like maintenance become much more difficult.

5. Industry Resources

Data centers are a very in-person industry with lots of conferences. We attended one hosted by Bisnow, but DCD (Data Center Dynamics) and PTC host large events several times per year. The vibe varies: Yotta in Vegas is networking-heavy, DCAC in Texas is more social, and manufacturer conferences (Eaton, Schneider) mix technical content with marketing. IEEE conferences are purely technical.

For staying current on industry news and research:

- DCD (Data Center Dynamics): News and industry updates

- Uptime Institute: Technical white papers and reliability standards

- 7x24 Exchange: Industry news and articles

- Green Street and TMT Finance: Market research and financial analysis (paywalled)

Eric Flaningham’s Primer on Data Centers is also a great piece for anyone looking to learn more!

- We were exploring startup opportunities related to data centers, particularly around supply chain & procurement. While we ended up deciding to shelve that idea, we learned _a lot_ along the way. Thus, this guide. ↩